Why Good Films Don’t Make Money: Blade Runner

When discussing films, there are few that bring out such exuberant and strong opinions as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. Originally released in 1982 to a dismal box office, making just over $41 million on a $28 million budget, it would become a film to be praised over the decades. Its sequel Blade Runner 2049, directed by Denis Villeneuve, not only mirrored the original in critical success but also financial failure, barely making it into the black after release.

The question still remains: Why? What is it about these films that made audiences afraid to purchase a ticket for movies made by great directors with amazing casts? To answer this, I sat down and watched them back to back in an attempt to further explore why good films don’t make money.

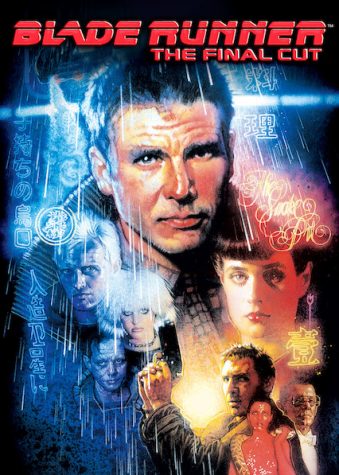

Quickly, let’s start with more history (yay). There are three versions of Blade Runner: The Original Cut released in 1982, The Director’s Cut released in 1992, and The Final Cut released in 2007. The version I watched was Blade Runner: The Final Cut, and I would say it is, for the most part, as good as its name has lived up to be. Harrison Ford’s performance as Blade Runner, Rick Deckard, is fantastic; it’s cool to see him in a role where he gets beat up consistently as opposed to someone like Indiana Jones or Han Solo. The music is some of my favorite in film history, specifically the main theme, but still, it’s all excellent and does nothing but add to the atmosphere of the dystopian future Ridley Scott beautifully crafted.

We learn that some of the Replicants, robot-human look-alikes who are used as slaves off-world, have implanted memories in their coding. Throughout the film, it is hinted that perhaps Deckard himself is not as human as he thinks. One method of presenting this idea is the use of unicorns. We see in one moment Deckard has to himself, he daydreams the mythical creature seemingly out of nowhere. His partner throughout the film, Gaff, is seen making origami of different animals, and at the end of the film, as Deckard is escaping with his love interest, a Replicant, Rachel, he sees that Gaff has left him an origami unicorn. This implies that he also suspects Deckard to be a Replicant, but this is left open to interpretation, never to be answered.

This is a great example of screenwriting that doesn’t stop the film or provide unneeded exposition. Not-so-great screenwriting can be found in movies like Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom, where the main villain literally stops our heroes in the middle of a scene to drop exposition out of nowhere.

The Final Cut’s biggest flaw, though, has to be its pacing. It unnecessarily lingers on simple shots, and it takes you out of the film. This directing style was incredible in Scott’s classic, Alien, because it makes you feel uneasy or uncomfortable watching it, as you never know what’s around the corner of the Nostromo. Here, it’s not effective because it will stay on a shot 5-10 seconds after all the main characters have left the shot, and while it may look nice, there’s nothing we need to see in these shots anymore for the story to make sense.

I’ll get this straight out of the way: I have a list of 12 films I consider perfect, and Blade Runner 2049 is on it. There was never a moment where I wasn’t fully immersed. The cinematography here might be the best of all time; it’s definitely near the top of the list. Ryan Gosling kills as lead K and works off all the other actors extremely well.

The way it cleverly subverts expectations while still telling one of the best stories told in film is incredible. For example, one of my main gripes was how similar K’s costume design was to Deckard’s in the original. As the story progressed it seemingly becomes clear that K is actually Deckard’s son, which I thought was cool, and made sense as to why they’d be dressed the same. Then we find out that Deckard had a daughter, and I realized the reason for the “lazy” costume design was to trick the audience into thinking one way, so they wouldn’t even suspect what we’d been told was a lie. Absolutely genius.

Both of these films are some of the greatest ever made, which is why it is of no shock to me that both films were box office bombs. These are not made for average moviegoers, but film lovers. They don’t rely on action scenes or jokes to keep the audience invested, but amazing storytelling that requires you to think and feel something when the credits roll.

Much like the Replicants in the future these films created, a regular moviegoer is a slave to the system of how modern Hollywood operates and doesn’t do much to try and change it. In a way, if you can hunt down and make sense of the many different ideas found within both films, you might be worthy of the title of Blade Runner.

"This is where the fun begins." If you're a big fan of film, TV, or the world of entertainment as a whole, you've come to the right place. This will be...