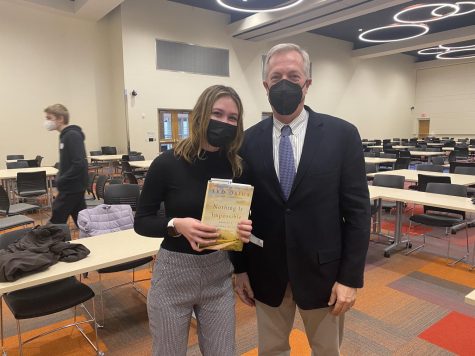

Former U.S. Ambassador To Vietnam Visits High School Students In Missoula, Montana

“Nothing is impossible,” as Ted Osius, former United States Ambassador to Vietnam, put it. However, 25 years ago a relationship between the United States and Vietnam seemed near impossible.

Vietnam had three times the number of bombs dropped on it than what the U.S. dropped on Europe and Africa during World War II. Many people could not imagine normalizing relations with the country after the Vietnam War, but the former U.S. Ambassador thought, “Wow, what would it be like to go to a place where we had such a terrible relationship?” This thinking made Osius one of the best U.S. Ambassadors.

Osius had been a diplomat for almost 30 years, U.S. Ambassador for three years, one of the first U.S. diplomats at the U.S. Embassy in Hanoi and the second openly gay ambassador. He also biked across Vietnam twice, deepened security ties between the countries, crafted trade, environmental, and law enforcement deals and ultimately helped heal the broken past between the U.S. and Vietnam. He has also written a memoir titled “Nothing is Impossible.”

Recently, Osius visited Missoula, MT, where he discussed his experiences with 25 students participating in an Environmental Exchange put on by the Mansfield Center and sponsored by the U.S. Embassy in Vietnam. He told the students, “I’m not here just to push paper. I’m here to change a relationship between a country of a hundred million and the United States.” Osius did just that.

Unlike many other ambassadors, Osius spent a large portion of his time meeting Vietnamese people. One of the ways he met people in Vietnam was through biking. He said, “I biked through the country a couple of times, but the first time I biked it was poor and everyone was kind of moving the pace of a bicycle. The second time was when I was an ambassador, there were all these cars and trucks and, and buses. It was a very transformed country.” Osius explained that throughout his time there, he was “able to see the arc of transformation of our relationship from almost nothing, no trade, very little exchange, few people going back and forth, to this kind of explosion in the relationship.”

Vietnam was a life-changing experience for Osius. He said, “I think Vietnam did change me. One of the things that it probably taught me was not to hold back, cause there’s a way in which diplomats are urged to sort of keep your head down, don’t make too many waves, don’t do anything too controversial.”

However, he said, “The best thing you can do is just be yourself. ‘Cause you’re not gonna be very good at trying to be somebody else, but you probably will be very good at being yourself.”

Osius described Vietnam as “the most marvelous, welcoming, exciting place.” While many countries, even the U.S., seem to get caught up in the past, Vietnam does an astonishing job of focusing on the future. Osius said, “There is this willingness just to look forward. They say, ‘close the door on the past and focus on the future.’ And people are really quite willing to do that.” He explained that even when he was there in the ‘90s he would, “encounter people who had suffered as a result of the war, they were really interested in talking about that, they were interested in talking about the future, they were interested in their children’s future and their grandchildren’s future, and are not very focused on the war.”

This incredible ability to focus on the future has led to the ability to become allies with a country we were once at war with.

One instance that demonstrates this reconciliation, as described by Osius, was when he traveled to a place where Vietnamese kids reside after being affected by Agent Orange, a chemical herbicide that the US dropped on Vietnam. While at the institution, a group of veterans wanted to talk to him. An uneasy feeling spread throughout Osius as he walked over to the group of veterans. However, the least expected thing occurred when he introduced himself. The Vietnamese Veterans, literally, threw their arms around Osius and embraced him. He said that instance is “surprising to many Americans, it certainly was to me, but many Americans go there and the warmth that is shown to us as Americans is quite astonishing.”

Another story that conveys this cultural difference is when Osius was riding his bike for the first time across Vietnam. He stopped on a bridge and, “below the bridge, there were these ponds and there was a woman, a little bit older than I, who I started talking with.” He asked the woman why there were so many oddly shaped ponds, The woman responded and explained that they were areas where Americans dropped bombs. She continued, and listed off how many villagers and family members died.

Osius said he began, “feeling worse and worse” and he told the woman, “I need to be honest with you, I’m American, and I work for the embassy.” Despite losing all of these family members and friends, the woman responded by saying, “We are all family.”

Osius explained, “I think that sort of embodies the spirit of forgiveness and reconciliation, that makes it so powerful.” He even told the Senate this story because he believes that “it’s important for people to understand that Vietnamese want to be friends with us. Ordinary Vietnamese people, even those who’ve suffered the most, want to be friends with us.”

The Vietnamese showed immense kindness towards Osius, and the former ambassador worked hard to rebuild the relationship between the two countries. He did this by facing the past so that a future could be rebuilt that would be stronger than ever. He said, “The truth is, ever since the war ended, or our part of the war ended, we’ve been gradually, gradually dealing with that past, and I insisted as Ambassador on being as honest as possible about that past.”

A few ways Osius faced the past was by cleaning up Agent Orange and helping to unite soldiers that passed away with their families.

There are large amounts of unexploded ordnance everywhere. Osius said, “It turns out it’s confined, there are places and you can clean it up. And so we’ve been involved now in a decades-long effort to clean it up.” This long effort to clean up the residue of Agent Orange is on its way to being completely finished. However, Osius said that we could still be more honest about those who were affected by it. He said, “I think the last challenge would be to be more honest about dealing with those who suffer the effects of Agent Orange, because we’ve helped, but not very much.”

In Vietnamese culture, if an individual passes away and their remains are not buried, “your soul wanders the earth forever.” So, Osius said, “We’ve started to do something we waited a really long time to do, which is to help the Vietnamese find those who they lost.” He went on to explain that the US “focused for so long, so unilaterally, on American losses and returning the remains of those who had been lost to their loved ones to help bring closure. But we didn’t do much about the Vietnamese losses, which were many many times larger. As many as three million Vietnamese died.”

Osius also focused on building up the country so that it had a bright future ahead by addressing the pressing issue of global warming. He said, “Vietnam is one of the five countries that would be most affected by climate change.”

He worked with topics such as agriculture and typhoons that are a result of climate change. Osius said, “We did a lot on the sides of climate change and the potential effects of climate change. We did a lot to study agricultural techniques involving rice.” He also did a lot in regards to water systems by studying “the effects of climate change on those water systems” by working “with those authorities that were trying to deal with the effects of massive storms, because Vietnam has been getting slammed again and again by these super typhoons that were really spawn as a result of climate change.”

Osius explained that working on improving the effects of climate change was “the biggest part of our aid program, but it was also a way that I think you could see the Vietnamese changing their mindset.” His philosophy on global warming is we “developed this world, created this problem” so we need to fix it. In regard to climate change, Osius said, “I think there’s so much that governments can do. And so much of the private sector can do so. Vietnam can be among those countries that could achieve its climate change targets, its net zero emission targets.” Recently, the prime minister of Vietnam made a major commitment to achieve zero carbon emissions by 2040. Which, according to Osius “is very ambitious for a developing country.”

Osius dedicated a large portion of his life to creating bilateral relations between the US and Vietnam. Six months after Osius left office, he was awarded the Order Of Friendship. For the Vietnamese, this is “the highest order and highest award that could be given to a foreigner.” Because he was “consistently a friend.”

In a remarkably short period of time, only 25 years, “we’ve gone from being enemies to being friends and security partners.” Osius described his experience as, “A great, I think, a wonderful story, that reconciliation is possible, and I was lucky enough to be part of it.” The exchange program with the Mansfield Center celebrates the anniversary of these restored bilateral relations.

This mindset that “nothing is impossible” is what keeps the world spinning. It allows people to form relationships that were once thought to be irretrievable and pushes the philosophy of closing doors of the past and focusing on the present and future, like the Vietnamese have learned to do. We should continue to be curious and receptive to change like former US Ambassador Osius, in order to make a greater impact on this amazing world we live in.

Hi, I’m Maggie Vann, and I'm a senior at Hellgate High School. This is my third year in Lance and first as Co-Editor. I’ve enjoyed expressing my creativity...